In the previous post, in which I reported on my conversation with Walburga Breitenfeld Shearer, I noted that Mrs Shearer’s mother, Johanna Breitenfeld, had been a member, with Theodor and Friedl Kern, of the Gemeinschaft, or spiritual community, founded by the philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand and led by his former secretary, Marguerite Solbrig, who was Johanna’s best friend. I’ve written elsewhere about Marguerite Solbrig and the Gemeinschaft, and also about Theodor and Friedl Kern’s involvement in it.

Searching online for more information about the community, I came across the recording of a talk given by Katherine Weir, one of its longest-standing members, at the annual retreat of the Society of the Sacred Heart in Mundelein, Illinois, in 2018. As Miss Weir explains, the Gemeinschaft was relaunched in 2007 as the Society of the Sacred Heart, or Herz Jesu Gemeinschaft, a lay community within the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest.

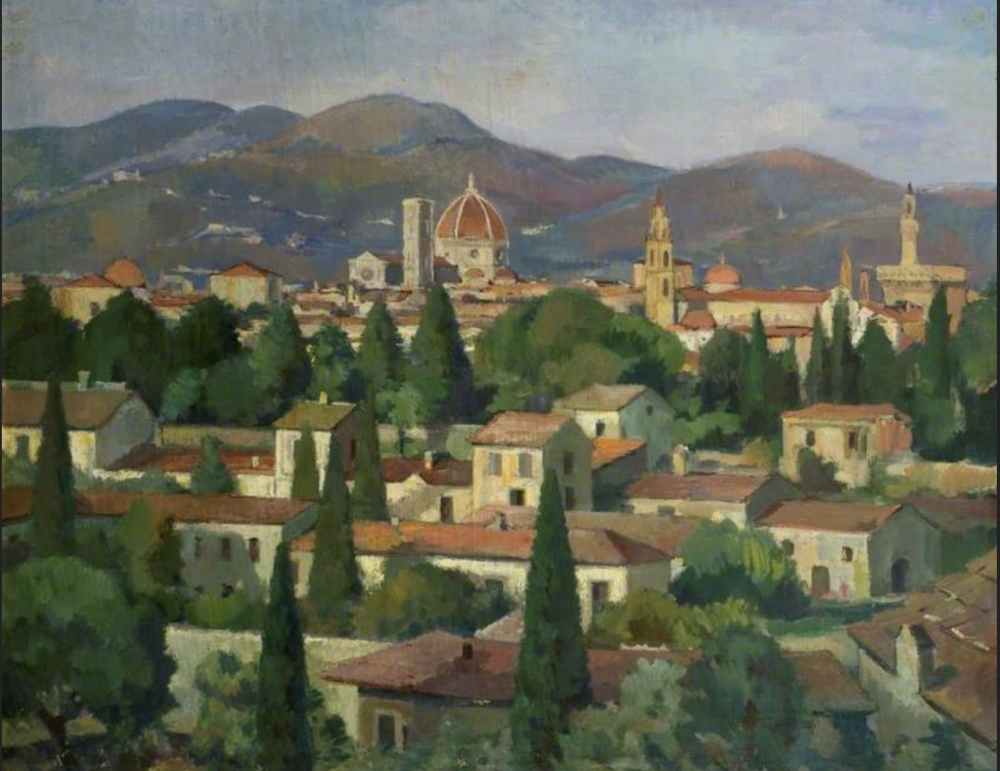

I wonder if this unfinished picture by Kern, of souls on earth and in heaven adoring Christ’s Sacred Heart, which I came across in the Smith collection, is meant to represent the community:

Theodor Kern, untitled/undated sketch (Smith collection)

Katherine Weir’s talk provides a fascinating insight into the origins of the Gemeinschaft, its activities, and its spirituality, which I believe had a profound influence on Theodor Kern and on his art. There’s a tantalisingly brief reference to Theodor and Friedl in the talk (highlighted in bold in my transcript below), and a mention also of Johanna Breitenfeld, under her title of Countess Schönborn. I was intrigued to learn that members of the community had secret names for each other: I wonder what Theodor’s was?

Katherine Weir at the Society of the Sacred Heart Annual Retreat, June 2018 (via)

Miss Weir notes that one of the main sources that she drew on in outlining the history of the Gemeinschaft was a book by Dr Wolfgang Waldstein entitled Herz Jesus Gemeinschaft, and a copy of it can be seen on the table in the photograph above. I would dearly love to get hold of a copy of this book, as I’m sure it includes information that could assist me in my research on Theodor Kern. However, it doesn’t seem to be available online, nor have I been able to find it in any lists of Dr Waldstein’s many published works. If anyone reading this can help with my search for the book, I’d be extremely grateful.

I’ve transcribed most of Katherine Weir’s talk below, focusing on those sections in which she tells the story of the original Gemeinschaft. The links, and the notes that follow, were added by me:

I was asked…to give you some background of the Community, and I have two sources. One is a book called Herz Jesu Gemeinschaft, that’s the Society of the Sacred Heart in German, and it was written by Professor Wolfgang Waldstein, who is the Governor of the entire Institute. He lives in Salzburg and is not well, and I won’t be seeing him this year, but he’s a wonderful, wonderful soul, and so my information, the early parts that I didn’t know, come from this book, but also from my experience knowing many of the wonderful souls that did. […]

It was a different time and a different place, but we all have the same longing, and that really was the meaning of the Community, if I’ve understood Dr Waldstein, that it was partly Dietrich von Hildebrand, in his philosophy, saying that there’s a personal longing, a call to holiness, and that leads to a search for a community of like-minded souls who wish to surrender to Christ, to kill their self-will and with God’s help seek His will.

Dom Eugène Vandeur (via Site-Catholique.fr)

So that was an idea already put out by von Hildebrand quite separate from the Institute. But the actual first founder of the Gemeinschaft was Dr Elizabeth Kaufmann, born in 1895. She was a social worker, and with a priest, Père Vandeur [1], she wanted to found a cloister in the world. She believed that there were women whose apostolate was in the family or in a profession, but they wanted to lead a deeply spiritual life in some kind of community. And she and Père Vandeur explored this but Rome would not accept this idea at that time.

And so, later, in Munich, Elizabeth did meet Dietrich von Hildebrand, and that friendship began to develop. And then there were a couple, Hermann Solbrig and his wife Marguerite, who were also close friends with Dietrich von Hildebrand. They were a deeply devoted couple to each other, but they were areligious. Hermann was a fallen-away Catholic, Marguerite was a nominal Christian. They were a wonderful couple who loved each other dearly, so that was another connection there. Now in 1919 there was a political uprising in Bavaria and Hermann was shot in the leg, a curable wound in our day, but in that time devastating. And as Hermann lay dying Dietrich von Hildebrand was at his side and he helped him return to his Catholic faith before he died. Marguerite Solbrig was devastated, and again Dietrich von Hildebrand stepped in to strengthen and console her, and Marguerite became a Catholic.

Leni and Balduin Schwarz (via Stephen Schwarz, ‘Why I Am Still A Catholic: From Born Catholic to Committed Catholic’, Goodbooks Media, 2017)

And then it happened that this combination of Dietrich von Hildebrand, Marguerite Solbrig, Elizabeth Kaufmann, they came together and with the help of a Benedictine monk , Alois Mager [2] founded the community, or in German called the Gemeinschaft. And it began to take shape. The official founding of the community or Gemeinschaft was in 1928, with Elizabeth Kaufmann as Superior. It was intended to help women who lived in the world and who had professions, but who wanted to lead a deep religious life. Then soon a young student of Dietrich von Hildebrand’s, Balduin Schwarz, he asked to join the community, and so men began to join the community. When Balduin Schwarz married Leni, it was then seen that the community could be open to married couples. And this was all in the early 1930s that this occurred. Since vows of poverty and chastity were not required, the emphasis was on obedience, but of course the evangelical virtues of poverty, chastity were also presumed for anybody wanting to lead a strictly spiritual life.

The members had religious names, and in private they used these names. Marguerite Solbrig was known as Mater Scholastica, Balduin Schwarz who was a philosophy professor, was called Frater Anselm. For many reasons, one, to protect the members who had a more public life, and also for fear of the Nazis, a very strict secretivity was preserved. Unfortunately that aspect lasted too long. We were really hidden away in secret from our own families. My own mother didn’t know to the day she died what I had been doing, and she suffered from that.

The Gemeinschaft members lived in Munich and other parts of Germany and also in Salzburg and other parts of Austria. World War Two had a great effect on the community. Dietrich von Hildebrand, his wife, Balduin Schwarz and his family, Marguerite Solbrig and her daughter Mücki, had to leave Europe and come to America. It’s probably the only good thing that Hitler ever did, at least from my perspective. Theodor Kern, also a member, from Salzburg, and his wife, went to England [3]. And, of course, this then opened up the Gemeinschaft to other people.

Elizabeth Kaufmann sadly was killed in an Allied air raid in Dresden, and thereafter Marguerite Solbrig became the Superior of the community. Now God works in very strange ways, and in the United States, von Hildebrand and Balduin Schwarz, met other good Catholics who were also seeking a deeper spiritual life, and they too joined the Gemeinschaft, the Community. So there were community gatherings at Central Park West and 105th Street in Manhattan, in the Forties, the Fifties and the Sixties […]

448 Central Park West, New York City, home to the Hildebrand, Schwarz and Solbrig families in the immediate post-war period (via google.co.uk/maps)

Not all members of the Community were famous professors. Some were mothers, caring for their children, elementary school teachers, women who came into Gemeinschaft households as housekeepers- they did all the cleaning and the cooking, and they eventually became beloved members of the Gemeinschaft. So it was all types of people came. There were businessmen, social workers, a scientist, several artists, and some of Dietrich von Hildebrand’s sisters, wonderful characters, joined the Community. In Europe there were also counts and countesses, even a princess, who kept telling me that she was from the poor side of the family. There was also Countess Schönborn. Countess Schönborn was the aunt of Cardinal Schönborn of Vienna. She was a social worker, and she fled to England during the War and died there, and was a wonderful, wonderful person, a true Countess.

Johanna Breitenfeld, Countess Schönborn (photo courtesy of Radka Ristovska)

There were families with children, some of whom were handicapped, and the parents needed to care for them, so nobody had an easy time. Since most of the members, even in New York, and certainly in Salzburg and in Munich, they lived together in a household, or nearby, it was easy to meet. So every week there was a community gathering to pray Vespers and instruction was given, prayers were offered for special intentions, especially for the dead, and there were long lists going down forever, praying for our departed and for relatives of the departed. Even a collection was taken, each giving according to his need.

Private instructions were given on a regular basis. You would go to meet with Marguerite or Balduin or whoever you found helpful, ready to answer questions, solve problems and offer advice, and some of them I think are saints in heaven because of all the phone calls they had to answer from people that needed help. Mater Scholastica died in 1969 and after, Edith Seifert [4] of Salzburg became the Superior of the Gemeinschaft, and she was known as Mater Assumpta.

Now Vatican II, in the middle of the Sixties, had a great effect on the Gemeinschaft, especially with the decree on lay spirituality. I don’t recall it being so focused on before that time. And so, under Edith’s guidance, the Gemeinschaft began to re-think its practices and, in effect, it gave up a lot of its strict monastic character and the Community began to accept new members who were not Benedictine oblates and there was less intrusion into private lives. But the help was always there, you could always find a kind, understanding, helpful person who would help you in a difficult situation.

Notes

- Dom Eugène Vandeur (1875 – 1968), Belgian monk and author of many books on spirituality.

- Alois Mager (1883 – 1946), Benedictine monk, philosopher and psychologist. See this post.

- This is slightly misleading. Theodor Kern only met his second wife, Friedl, when they were both refugees in London in the 1940s.

- Edith Seifert (1909 – 1997) was the mother of the philosopher, and student of Dietrich von Hildebrand, Josef Seifert, who has been one of my key informants about Theodor Kern’s involvement in the Hildebrand circle. See this post.

Update

Wolfgang Waldstein

I’ve found a reference to the book about the Gemeinschaft that was mentioned by Katherine Weir in her talk, in Wolfgang Waldstein’s memoir Mein Leben: Errinerungen (Media Maria Verlag, 2013). On pages 234-235, Dr. Waldstein writes (my translation):

A longstanding concern of the Herz Jesu Gemeinschaft has been to create an anthology from the early writings of this community. Dr. Ernst Wenisch had worked on it for many years, but ultimately could not get his work due to his longstanding illness. The result, which is the book Herz Jesu Gemeinschaft, Auswahl aus frühen Schriften [The Sacred Heart Community: Selection of Early Writings], was published in 2006 by the Herz Jesu Gemeinschaft in the Institut Christus König und Hoherpriester. It is not available in bookstores and can only be obtained from the Institut Christus König und Hoherpriester in Bayerisch Gmain.

I plan to contact the Institute to see if they have a copy available for sale.

Further update

Unfortunately, the Institut Christus König und Hoherpriester has informed me that the book in question is only available to members of the Society of the Sacred Heart. I contacted Stephen Schwarz, who was so helpful to me last year in providing information about Theodor Kern’s membership of the Gemeinschaft. He does not have access to a copy, and does not know whether it includes any reference to Kern. Stephen also helpfully pointed out a few errors in what I’ve written about the Gemeinschaft, which I’m happy to correct here.

Apparently it is not strictly true to say that the Gemeinschaft was founded by Dietrich von Hildebrand, though, as Stephen writes, ‘his ideas were probably part of the spirituality that originally formed it.’ Stephen adds that, during a good part of the time that he attended meetings of the community in Marguerite Solbrig’s New York apartment, von Hildebrand did not actually attend, though he joined some time later. Marguerite was the leader of the community, from the time of its inception until her death. Stephen confirms that one of the founders was Elizabeth Kaufmann, who is mentioned by Katharine Weir in her talk (see above). Elizabeth Kaufman was, in fact, Stephen’s godmother; von Hildebrand was his godfather. Finally, Stephen corrects the impression given in Miss Weir’s talk that members of the Gemeinschaft had ‘secret’ names for each other. Their names in the community were simply those they took as oblates in the Order of St. Benedict. Stephen adds that von Hildebrand was known as Frater Petrus, while he himself was Frater Joseph.

‘Frater Placidus’

Yet another update to this post. Stephen Schwarz has been in touch again, to inform me that Theodor Kern’s Benedictine oblate name was Frater Placidus.