On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, 27th January, it has become customary to name specific individual victims of the Nazi genocide, so that they are not forgotten or lost in the anonymous statistics of mass murder. Today I name Ida Waldek, who was Theodor Kern’s patron and supporter in Vienna in the 1930s, and who was murdered by the Nazis, either at the transit camp of Izbica near Lublin or at Theresienstadt concentration camp near Prague (sources differ), on 15th May 1942.

As I’ve noted in earlier posts, Ida Waldek, née Zifferer, was born on 28th October 1880 in Bystřice pod Hostýnem in Moravia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Her parents were Josef (known as Pepi) and Julie Zifferer. Ida had three brothers – Bruno, Alfred and Paul. Bruno died in 1924 at the age of 50. Alfred, a medical doctor, emigrated to the United States and died in New York in 1940 at the age of 65.

Paul Zifferer

Ida’s brother Paul Zifferer (1879 – 1928) was a novelist, diplomat, journalist and art critic. Educated in Paris, he became part of the ‘Jung Wien’ circle of writers. After the First World War and the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between Austria and France, Zifferer was appointed as literary attaché to the Austrian legation in Paris. According to his Polish-born wife Wanda, née Rosner, the first initiatives towards establishing the Salzburg Festival took place in their salon in Paris.

I don’t know where Ida Zifferer studied, but she must have had at least a university education, since later sources refer to her as ‘Frau Dr Waldeck’. Ida was married to Bohemian-born Dr Karl Waldek, son of Moritz and Regine Waldek, who held a senior position with the Austrian Railways Ministry. It’s unclear whether Karl and Ida had any children before his death in 1918 at the age of 46. A number of Karl Waldek’s relatives would be murdered in the Holocaust: his niece Marianne died in the Lodz ghetto in Poland in 1941 and his brother Gustav was killed at Theresienstadt in 1942.

Wattmangasse, Hietzing, Vienna

Established in a house in Wattmanngasse in the Hietzing district of Vienna, not far from Schönbrunn Palace, the widowed Ida Waldek became a patron of the arts and her home the location for a regular salon for writers and artists. She was a published writer herself, producing an undated volume of stories under the title Die Offenbarung (‘The Revelation’) and a novel, Ihr Kind (‘Your Child’), which appeared in 1909. According to one source, in both texts ‘realistic narration is masked by modernist tones’. These two books are apparently discussed, alongside those by her brother Paul, in Libor Marek’s 2018 book Zwischen Marginalität und Zentralität. Deutsche Literatur und Kultur aus der Mährischen Walachei, 1848-1948 (‘Between marginality and centrality: German literature and culture in Moravian Wallachia, 1848 – 1948’).

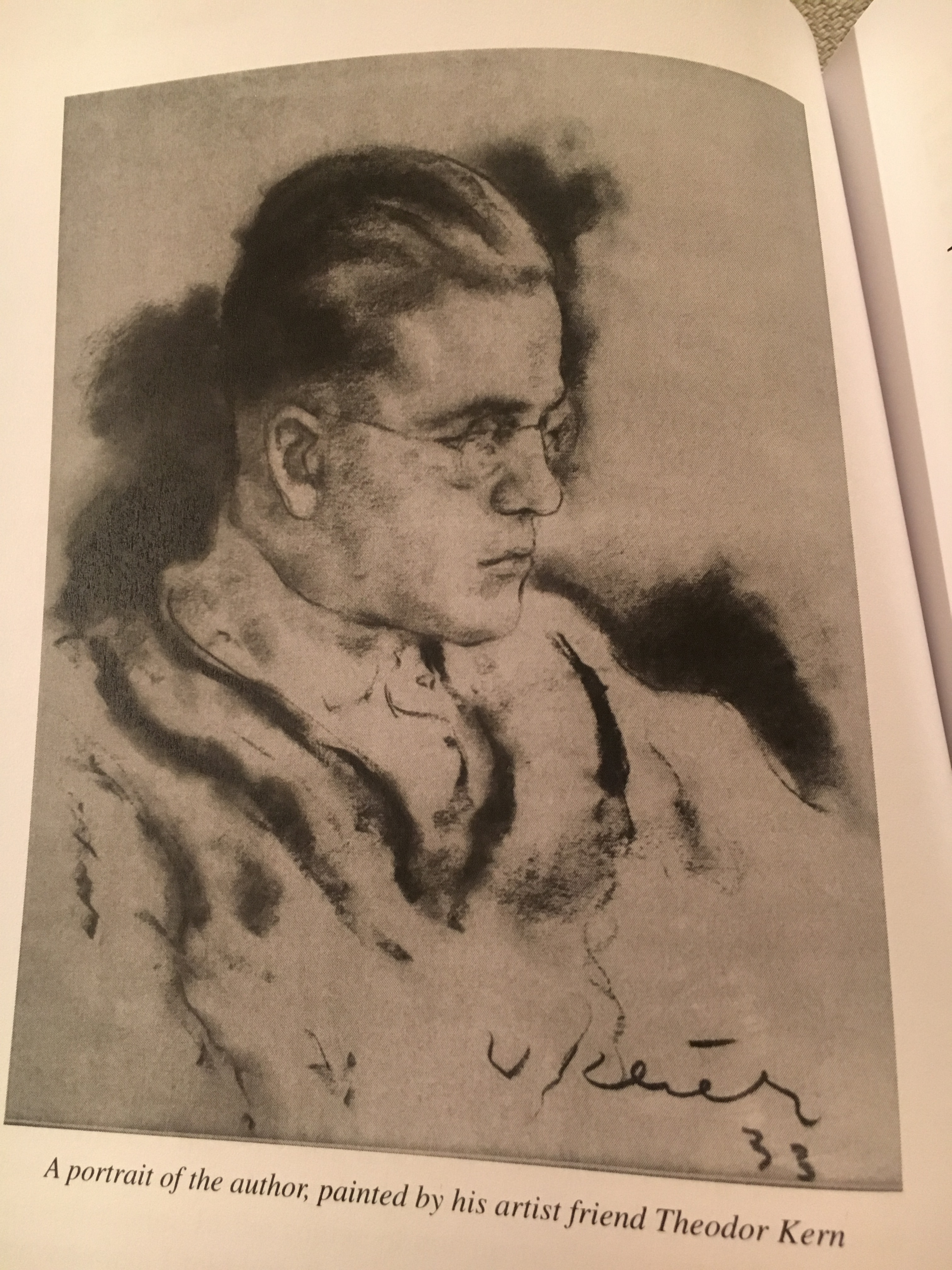

Theodor Kern’s 1933 portrait of Hellmut Laun, from Laun, H. (2019) ‘How I Met God’, tr. Fritz Wenisch, New Hope, Kentucky: New Hope Publications

It was through Ida Waldek that Theodor Kern met and befriended Hellmut Laun, who would convert to Catholicism partly under Kern’s influence. On arriving in Vienna from Innsbruck in the early 1930s, Laun lodged at Frau Waldeck’s home, as he recalls in his memoir [1]:

I had taken a room in Hietzing, as I was not looking for anything more than proximity to the factory and a quiet location. I found both of these in Wattmanngasse with Frau Dr. Waldeck, a single widow, who immediately introduced me to her large circle of Viennese friends and acquaintances. Dr Waldeck was…still organising a ‘salon’: that is, she held a weekly meeting to which she invited her friends. These were young, mostly poor artists, such as Franz Lerch and Theodor Kern, whom she also supported financially… Anyway, she was a patroness, and the people who came to her were of all ages and education, but all of them artistically and intellectually active.

Later in the book we learn that Theodor Kern was an ‘old acquaintance’ of Ida Waldeck’s and that he rejoined her salon on returning from his first spell of living in England, which took place shortly after Helmut Laun’s arrival in Vienna. I imagine that Kern knew Frau Waldek from his time as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in the early 1920s. Laun relates that Ida Waldek looked forward to her former protégé’s return with some trepidation:

Frau Waldeck, herself a liberal Jewess, told us some strange things about him before his impending arrival. He had been a painter for a long time in Paris, and led a fairly free life there, but had changed completely in England. It had come to her ears that he had even lived for a while in a monastery, and in any case was completely transformed, so that she now looked forward to his return with rather mixed feelings.

Any misgivings that either Ida Waldek or Hellmut Laun had were soon overcome when Kern turned out to be ‘a cheerful person [who] had a good sense of humour and talked interestingly about his experiences abroad.’ Laun adds that Kern ‘now began to appear regularly and was always served a particularly large piece of Schnitzel, since on other days of the week he rarely had enough to eat…he also came quite often during the week to see Frau Waldeck, who acted as his protector.’ Laun also relates that it was at Ida Waldek’s salon that he first met the philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand, a close friend of Theodor Kern as well as a leading campaigner against Nazism and antisemitism, and another key influence on Laun’s conversion.

Dietrich von Hildebrand

When that conversion took place some time later, ‘Frau Waldeck was the first to know … and of course that soon spread to all the people in her circle who passed through her house. Frau Waldeck was Jewish, but not a believer. Her reaction was neutral, except that she, …could not understand how one could take the step that I had taken in the face of the political situation.’ However, Laun writes elsewhere about a ‘clever and pretty niece’ of Frau Waldek’s, ‘a pharmacist’s daughter with a double doctorate’, who was a frequent visitor to the house in Hietzing, and who herself would convert from youthful radicalism to devout Catholicism, emigrate to England and join a religious order. I’ve yet to discover this woman’s name or what became of her.

Although Laun notes that his landlady was initially surprised and concerned about his own conversion, and even consulted a psychiatrist on his behalf, he also informs his readers that she herself would later be baptised into the Catholic faith.

At some point, Ira Waldek moved from Wattmangasse to Marc-Aurel-Straße. It was her last known address in Vienna. After the Anschluss of 1938 she was deported, either to Izbica or to Therienstadt, where she would die.

May she rest in peace and may her memory be a blessing.

Izbica

Theresienstadt

- Hellmut Laun, So bin ich Gott begegnet, Franz Sales Verlag, 2010 edition (my translations)