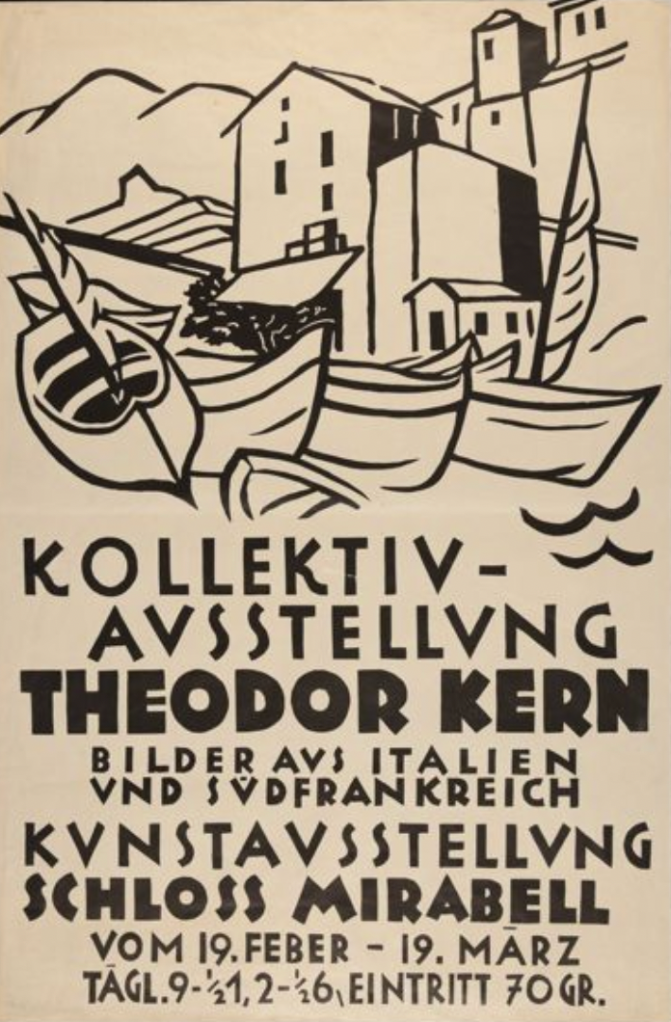

The folder of Kern-related items belonging to the late Jean Watts (see the previous two posts) includes a copy of the catalogue for an exhibition entitled ‘Theodor Kern in Retrospect: Paintings, Sculpture and Glass’, which was held at what was then Luton Museum and Art Gallery and is now Wardown House Museum and Gallery. The exhibition opened on 17th August and closed on 15th September. Unfortunately, the year is not mentioned, but since the notes imply that the artist was still living, I assume this was the retrospective exhibition which took place in 1968, just a few months before Kern’s death in February 1969, and which I mentioned in this post.

The exhibition catalogue is an extremely useful resource, both in providing a detailed list of the 70 or so paintings, sculptures and pieces of stained glass which the artist selected to represent his long career, and in the additional information on the back page about the locations in England where Kern’s public works – his murals, stained glass windows and sculptures in wood and stone – can be found.

Theodor Kern was interviewed for the Tuesday Pictorial, a local newspaper, at the time of the exhibition, which the resulting report describes as presenting a combination of traditional and more modern styles, with a predominance of religious themes. The dates of the paintings range between 1928 and 1968, the stained glass pieces are from the period 1945 to 1948, and the sculptures were created between 1945 and 1968.

It would take a good deal of time and effort to identify all of the items in the exhibition and it would probably prove to be an impossible task, since the items on display were available to purchases, with prices ranging from 15 guineas for a 1964 plaster head of Christ to a 100 guineas for a 1929 painting of a Sicilian village square, so it’s likely that a number ended up in private collections. Even among those that belonged (or would eventually belong) to public collections, Kern’s tendency to use the same or similar generic titles (‘Annunciation’, ‘Madonna and Child’ ‘Composition’) might hamper any effort to confirm their precise identity.

Nevertheless, a few of the paintings are certainly identifiable with known works by the artist. ‘Polish Bride’ (No. 46) which Kern began in 1930 and was still adding to in 1968, is definitely this beautiful portrait, now in the Wardown House Collection in Luton:

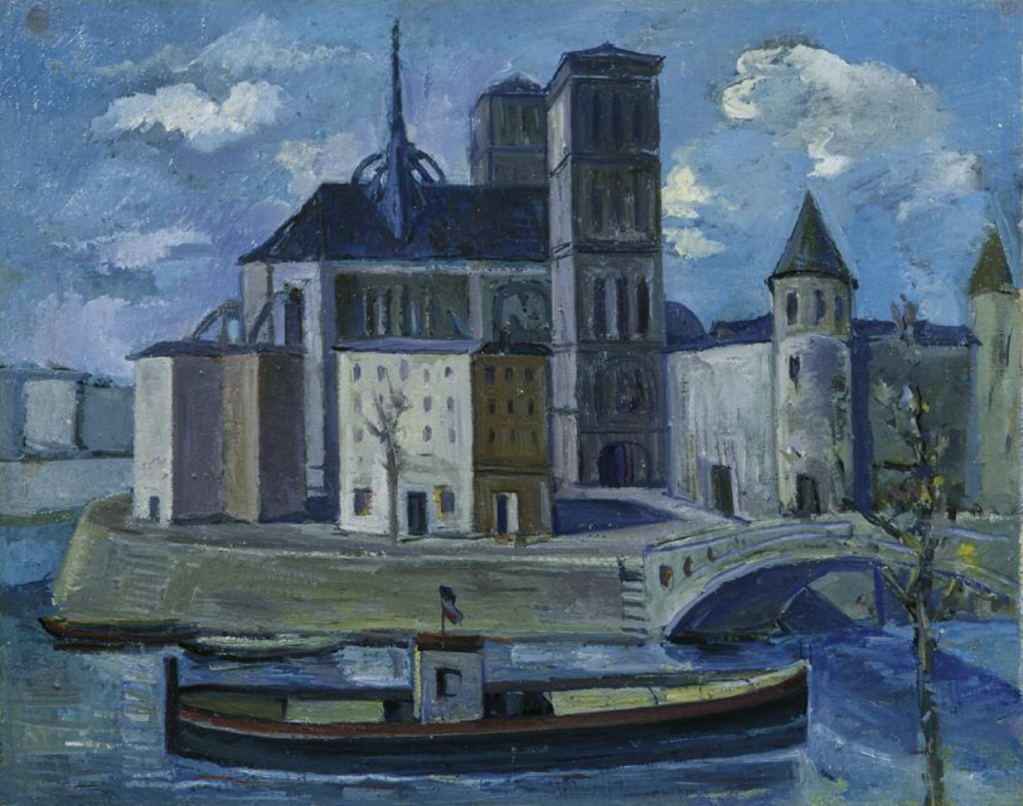

‘Harbour at Mentone’ (No. 9) from 1929 is almost certainly this picture, also owned by Wardown House:

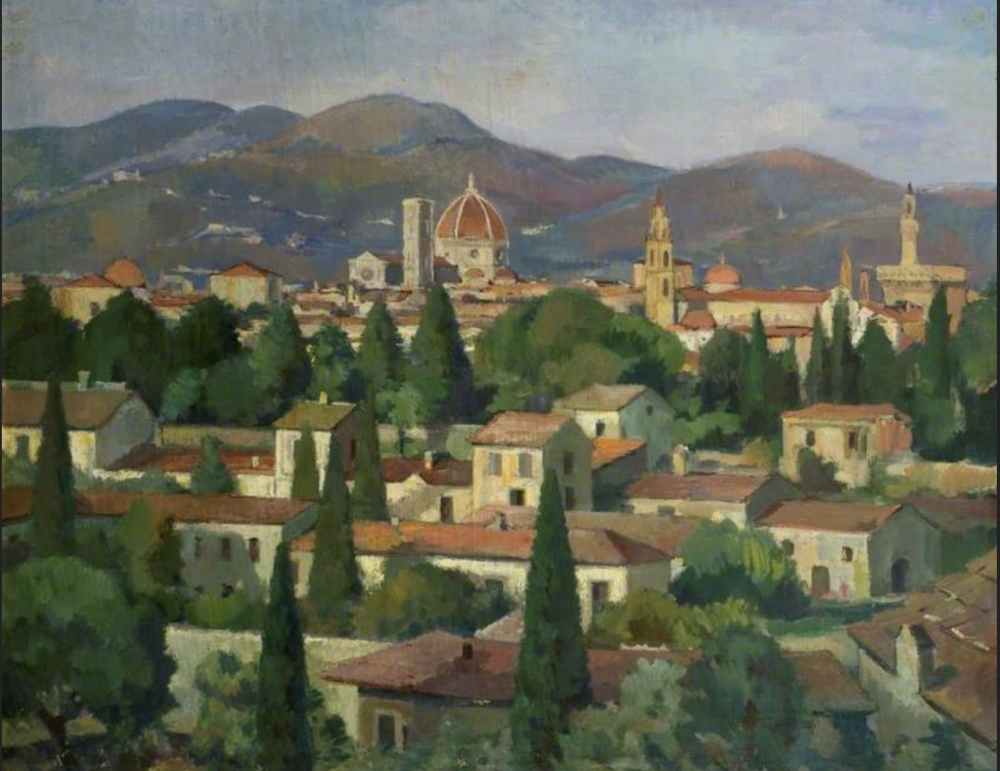

Theodor Kern painted more than one view of Positano, in different styles, but the picture from 1929 (No. 22) is certainly this one, also in the Luton collection:

I wonder if the Michael Braunfels, painted in 1967 playing the flute (No. 20) was the Austrian-born composer of that name (though he was better known as a pianist), and if so how Kern came to be painting his portrait in 1967?

Finally, I wonder whether any of the three stained glass panels in the exhibition with the title ‘Lovers’ (Nos. 2, 6 and 7) were based on the preparatory drawings that I came across recently in the Smith Collection, and which I wrote about here:

Sadly, I haven’t been able to find reproductions of the two paintings singled out for special attention by the local newspaper reviewer, either the ‘strikingly different’ ‘Wild Emotion’, ‘its colours more vivid than those Mr. Kern normally uses’ or ‘Refugees’, ‘where the agonised mother is pushing forward out of the dark past into an unknown future’.