Following on from my last post, about Kern’s Salzburg period, the next section of Ziegeleder’s biographical account of the artist is entitled ‘Jahre der Wandlung 1931 – 1938.’ This is my fairly loose translation:

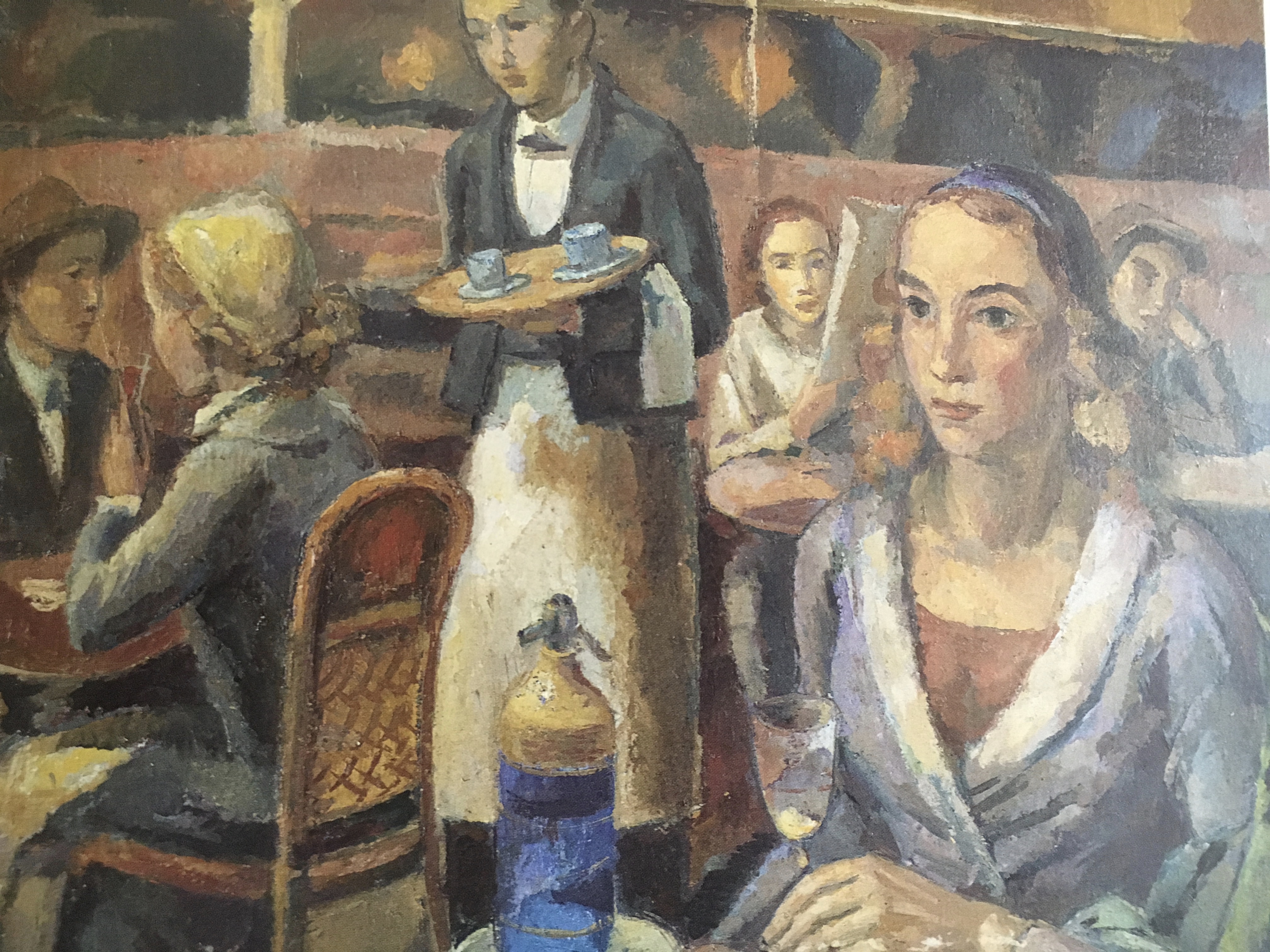

1931 was the year of major change in Kern’s life, and, surprisingly, it was Paris, where the younger generation of artists from all over Europe were at work, that provided the setting. Into this wild, unconventional, life, outwardly troubled by financial troubles but somewhat relieved by occasional sales of portraits in Parisian cafes, there came a young Swiss writer, P.-W. M., described as a kind, helpful and unselfish person. The details of how this friendship came about are unclear, but it’s known that the two men spent their nights walking and philosophising through the streets of Paris and by the Seine. One morning, Kern was standing in front of the gate of a Benedictine monastery, where he knew a monk who spoke German. But he waited a long time, and eventually, tired of waiting, Kern told himself that God could be served anywhere, and left. But from this time onwards Kern was a different person. Of course, he was already a Catholic and from an old Catholic family, so it would be inappropriate to speak of a conversion in the sense of a change of faith, but now he turned to a life of profound piety and humility, for which there were certainly parallels in his father’s family. In this religious spirit he would live his life as a man and an artist until its God-given end.

Theodor Kern, ‘French Café’, 1931 (Wardown Park Museum, Luton)

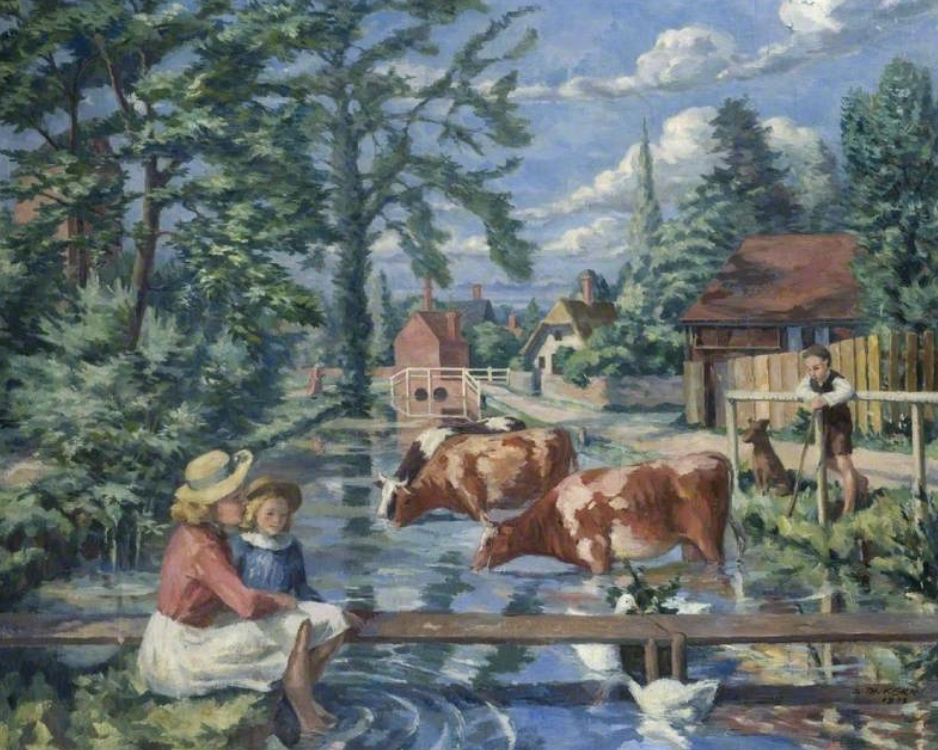

At just the right time, an invitation from England reached Kern in Paris. Some time before, he had met members of an English family who were on holiday in Salzburg, and whose portraits he had painted.The pleasure that these pictures gave in England earned him an invitation and the prospect of further portrait assignments. Kern soon set off, though he returned to Paris briefly to finally close up his lodgings there, and then stayed for a time in a bungalow in Newbury, to the west of Windsor, where he led a simple but meditative life. When the author visited him in England during the summer months of 1933 – the visit lasted several months – he had already moved to Windsor and was living in a small lodging house. At the same time, he was beginning to move once again in well-connected artistic circles, which would serve him well in 1938. In this early English period he created a large number of portraits, but above all landscapes, extremely delicate watercolours, of Windsor, Eton, Slough and other places. His watercolour technique was particularly suitable for capturing the delicately nuanced shades and clear, damp air of the English landscape. He even taught at Eton College and was also keen on restoring old paintings.

Theodor Kern, ‘Blick auf Windsor Castle’, 1933

His mother’s illness and death brought Kern back to Salzburg in 1934. While there he fulfilled a number of fresco and portrait commissions, but soon afterwards he made Vienna his main home. The author still remembers well his studio in the makeshift, converted attic of a house in the Rotenturmstraße. In this final and definitive move to Vienna several considerations played a decisive part. Until 1937 Kern probably maintained his small apartment in the family home in Salzburg, which now partly belonged to him, but after his mother’s death this refuge was no longer available, though his sister’s door was always open to him. His memories of Salzburg were also an obstacle to the consistent pursuit of his new path. His circle of friends, which in Salzburg had been dominated by the Schuchter family, in Vienna had Professor Dr. Dietrich von Hildebrand as its dominant personality, and this circle also helped Kern to progress and become established in his new-found mental attitude and spiritual strength.

Rotenturmstraße, Vienna

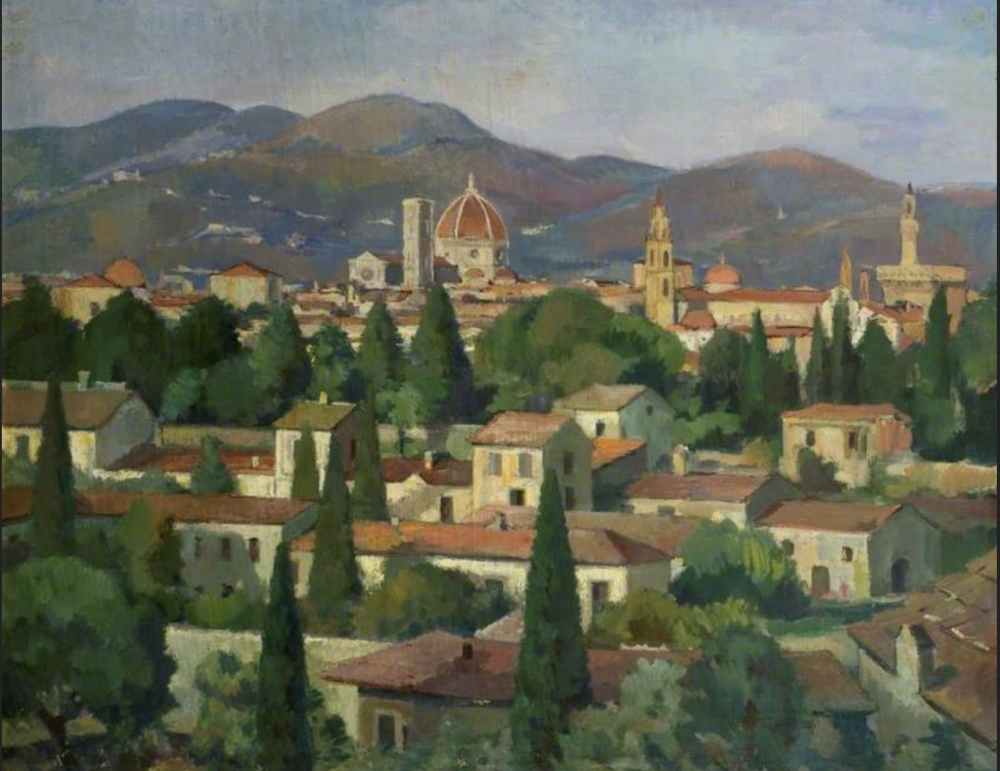

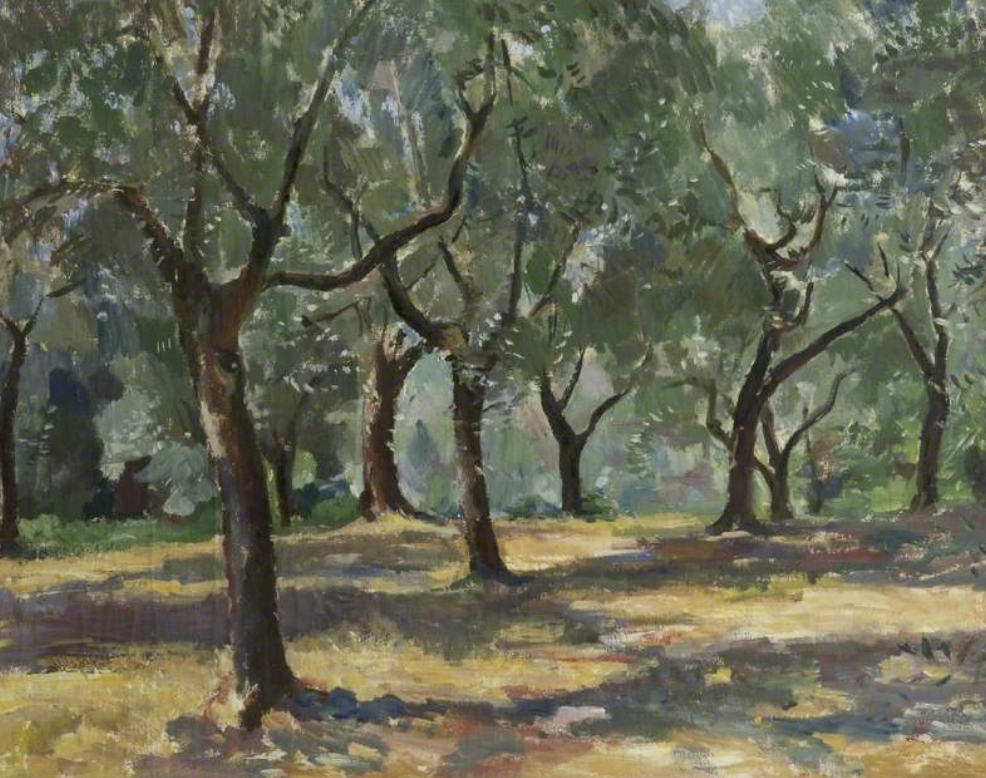

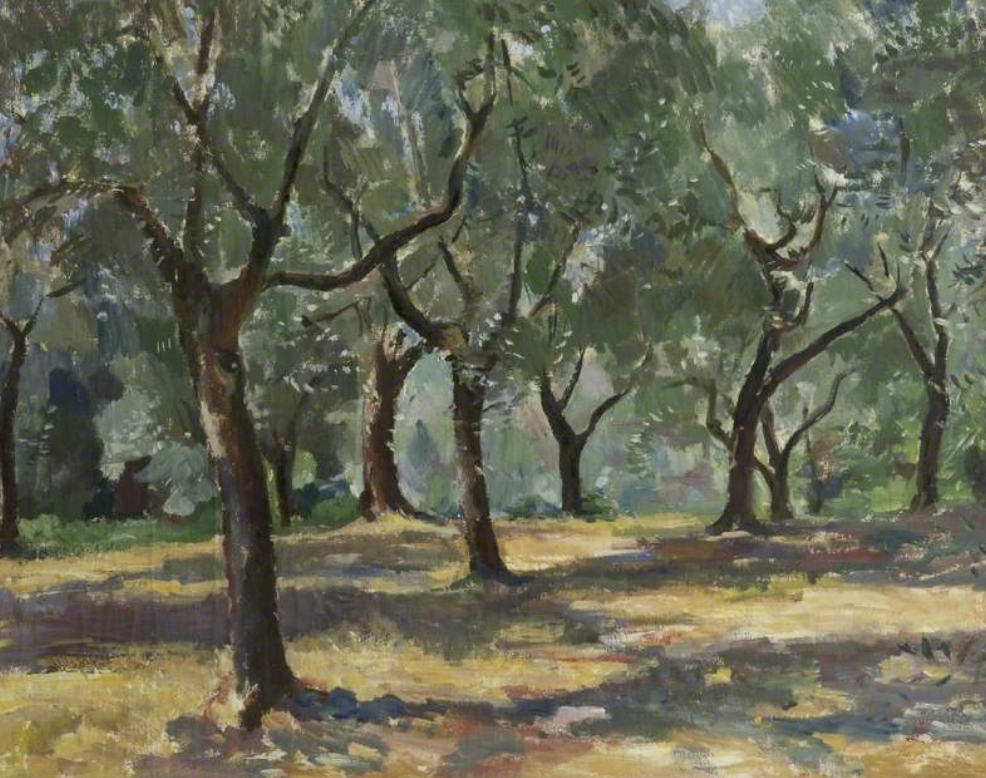

Among other things, Kern was greatly indebted to Dietrich von Hildebrand for an extremely happy artistic retreat of several weeks in 1935 at Panon Halma, an impressive Hungarian Benedictine monastery, magnificent and rich in treasures, where he was a guest and in return gave the abbot lessons in German conversation. Kern remained a faithful friend of this abbot until his death in South America. Moreover, Kern was also a guest at Hildebrand’s villa in Florence, where in 1936 he completed a number of beautifully composed and colourful landscapes in oil. They recall his early Salzburg period, even as they demonstrate the further development of his artistic skill; and indeed Kern never denied either his beginnings or his development: far from it. In Vienna Kern also frequented a circle of artists and intellectuals interested in the arts and brought together by Frau Dr W., a patron of the arts. This was not a time of restless creation, but rather a time of thinking, meditating and discussing. It is true that portraits and compositions were created, but Kern himself never talked or wrote about this time in Vienna, and it is also known that he destroyed much of his work from this period. From this it might be concluded that he felt there was still a gap between his spiritual state and its adequate artistic expression, which was yet to be achieved and therefore remained unsatisfactory.

Theodor Kern, ‘Wood, Hungary’, 1936 (Wardown Park Museum, Luton)

As the year 1938 approached, Kern was confronted more and more with the imminent fate of those who would eventually emigrate. Although he had always been apolitical, he saw his circle of friends and confidants increasingly faced with the consequences of the political situation, which in the end also threatened him. He was not just an artist, he was also human, and he tried to do God’s will, wherever and however he could. He escorted a frightened family across the border to Czechoslovakia, helped a young priest to burn documents and files, brought a priest of Jewish descent safely across the frontier, and finally escaped himself to Trieste himself, accompanied by somebody who was under threat, and then alone to Florence, where he first stayed at the Hildebrand villa. In the autumn of 1938 he was allowed to travel to Switzerland, to the home of Balduin Schwarz’s family in Fribourg, from where he finally reached England via Paris, thanks to the help of his former English friends.

The author has wrestled with the question of whether or not he should describe these years of great change in the present account. He takes responsibility for them on the grounds that this biography would otherwise remain incomplete and that it would otherwise be difficult to justify the life that Theodor Kern created for himself. Some names have been deliberately omitted, while others, whose bearers are proud of their willingness to help Kern, have been legitimately made known. Kern was bold in fighting, as an artist, for his art; but in other ways, he was by no means quarrelsome or even militant, but rather amenable, tolerant and devout. It became apparent that it was important for this objective account of his life to enable the reader to understand his subjective decision to abandon his homeland.

Kern’s ‘conversion’: a footnote

Ziegeleder points out, in a note to the above account, that not all of Kern’s family were Catholic: his mother Ottilie, who was from Thuringia, Germany, was Protestant. He also notes that there is an alternative version of Kern’s encounter with the Benedictine monk in Paris, in which it was the monk himself who, ‘mindful of the value of artistic creation, and especially of ecclesiastical art’, made the point that God could be served anywhere. I find Ziegeleder’s account of this transformative moment in the artist’s life rather compressed and enigmatic. Karl Heinz Ritschel’s version, while obviously drawing on Ziegeleder as a key source, is more expansive, and makes it crystal clear that Kern was actually seeking admission to the monastery – he wanted to become a monk:

Early one morning, Kern stood at the door of a Benedictine monastery and waited for a monk he knew; but he did not come for a long time. Kern, who wanted to be admitted to the monastery, went away and told himself that he could serve God everywhere. A second version goes that the monk advised the artist to serve God in his art. In any case, this change was extremely swift and decisive. For the remainder of his life Kern was deeply religious.