In the absence of access to Theodor Kern’s correspondence, an alternative method for researching his networks of friends and contacts has been to follow up the names mentioned in his widow Frieda’s will of 1980. While some of these have turned out to be neighbours and friends in the Hitchin area, others were further afield, and have confirmed my intuition that, despite their decision to remain in permanent self-enforced exile in England, the Kerns maintained contact with Austria, and with some key figures in the European Catholic intelligentsia, particularly those in the circle around Dietrich von Hildebrand. Among those to whom Frieda Kern left items that had belonged to her late husband, including some of his art works, were the Hildebrand scholar Dr Josef Seifert and his mother Dr Edith Seifert, Dr Stephen Schwarz, the son of Hildebrand’s student Balduin Schwarz and his wife Leni, as well as the Catholic jurist Wolfgang Waldstein, all of whom were living in Salzburg at the time. I’m in contact with Stephen Schwarz and Josef Seifert, both of whom have been extremely generous in sharing with me their memories of Theodor Kern. I’m also in the process of reading the memoirs of Josef Seifert’s grandmother, Johanna Schuchter, and of Wolfgang Waldstein, to see whether either make any reference to the artist, whom they both apparently knew well.

I’ve been intrigued for a while by two other names that occur in Frieda Kern’s will. Frieda left a ‘very dark wooden Madonna’ to Miss Walburga Breitenfeld, and a ‘small gilded Madonna and Child’ to Mr. Hubert Breitenfeld, for both of whom the will gave an address in Chiswick. The names sounded Austrian, or at least Germanic, so how did they come to be living in England, and how did the Kerns know them?

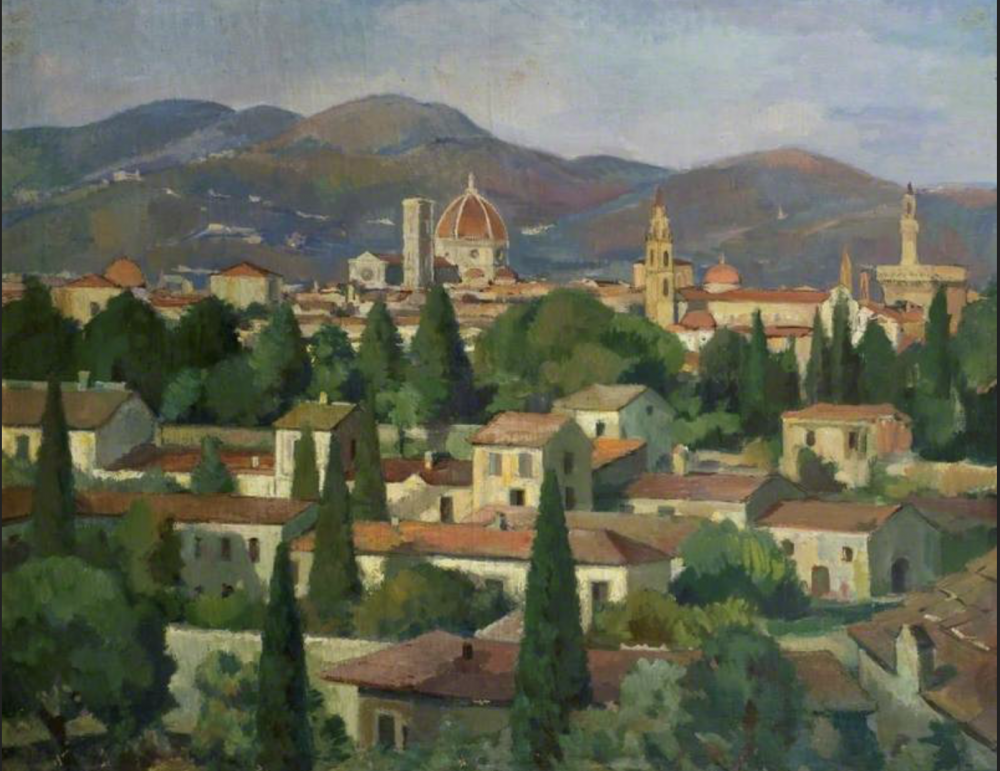

Chotek family mansion, Dolná Krupá, birthplace of Johanna Breitenfeld (via lesgravereaux.marret.co)

I found my first clue at, of all places, a website about the British peerage. It turned out that Hubert and Walburga were the children of Walter Breitenfeld and his wife Johanna, who had been born into the Austro-Hungarian nobility as Johanna Gräfin von Schönborn-Wiesentheid. Walter was born in 1884 in Vienna and Johanna in 1889 in Korompa, near Dolná Krupá, then a Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (today in Slovakia), the younger of the two daughters of Count Franz von Schönborn-Buchheim-Wolfsthal and his wife Gabrielle, née Chotek. According to her obituary in The Independent [1], Johanna and her sister grew up in the remote Burg Schleinitz, then in southern Styria, now part of Croatia:

That widely branched Central European family has not only recently celebrated their 800th anniversary but has remained consistently Katholisch. The Schönborns and Choteks were great patrons of the arts, respectively employing Tiepolo and sheltering the impoverished Beethoven.

The obituary continues:

Johanna studied psychology and philosophy at the University of Vienna; the eminent Charlotte Bühler and Rudolf Allers were among her teachers. The soup kitchens of post-First-World-War Vienna provided the first practical application of her studies. While her sister married Prince Pallavicino in Rome, she married, in 1928, a ‘commoner’, Walter Breitenfeld (1884-1971), whom she had met at the university and who later played a prominent role in Austrian Catholicism as a lecturer in social studies at Salzburg’s Catholic University and in vain opposition to the growing pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic trend among Austrian intellectuals in the inter-war years.

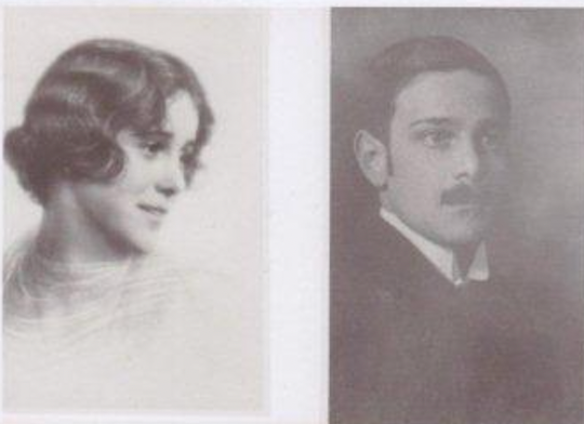

Johanna and Walter Breitenfeld (photograph courtesy of Radka Ristovska, added 11.09.21)

It was this anti-Nazi activity on the part of Walter and Johanna Breitenfeld that brought them into contact with the German Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand, and through him, I believe, with Theodor Kern. I’ve found references to the Breitenfelds both in Hildebrand’s own memoir My Battle Against Hitler [2] and in The Soul of A Lion [3], the biography written by his widow Alice von Hildebrand. Alice writes that, when his opposition to the newly-installed Nazi regime began to make von Hildebrand’s continued residence in Germany untenable, he made a number of unsuccessful attempts to find work, and a new home, in Austria:

In October 1933, Dietrich once again boarded a train going to the Viennese capital, a flicker of hope in his heart that this time he would succeed. Through friends he had made the acquaintance of a man named Breitenfeld and his lovely wife Johanna (née Schönborn, a close relative of now Cardinal Christoph Schönborn), who both shared his political views and concerns. They invited him to spend a few days with them at their residence close to Saarfelden and generously offered him the use of their apartment in Vienna while they were still vacationing. Their kindness and help, which extended over weeks, was God-sent and proved to be invaluable when Dietrich and his family moved to Austria at the end of the month.

Saalfelden, Austria (via wikipedia.org)

Von Hildebrand himself was somewhat more circumspect in his assessment of Walter Breitenfeld. His memoir describes their first meeting:

Walter Breitenfeld picked me up at the train station in Saalfelden and drove me to his country house which sat on a large property. He was a man of about fifty-five years. He wore the traditional Austrian dress, and in general there was something outspokenly Austrian in his speech. But most importantly, he was an ardent Austrian patriot. We were very much in agreement about Nazism, which to my delight he rejected completely.

[…]

Breitenfeld was certainly for Dollfuss, but not to the degree I would have liked. He and Dollfuss had previously been colleagues, when Breitenfeld had held the same position in Burgenland as Dollfuss had had in Lower Austria. For this reason, he felt himself to be at least equal if not even superior to Dollfuss. He was an enthusiastic monarchist, and here we were again very much of one mind. He was also a very committed Catholic, which of course greatly won me over for him. He had previously served as president of ‘Logos’, the Catholic intellectual association in Vienna with which I had already been familiar for many years. Breitenfeld struck me as a little too self-assured and at times he could be too sweeping in his judgements. He was also not entirely free of a certain anti-Semitism. These qualities certainly made me uneasy.

Yet he and his wife were very friendly to me, truly receiving me with the greatest warmth. They even offered to let me stay at their residence in Vienna located on Gumpendorfer-Strasse, with which I was quite familiar. They gave me the key and urged me to make myself completely at home. Breitenfeld was not close enough to Dollfuss to provide me with an introduction, nor was he able to contribute any important suggestions regarding my plans. But the days with him were stimulating and the relationship to him and his wife delightful and rewarding.

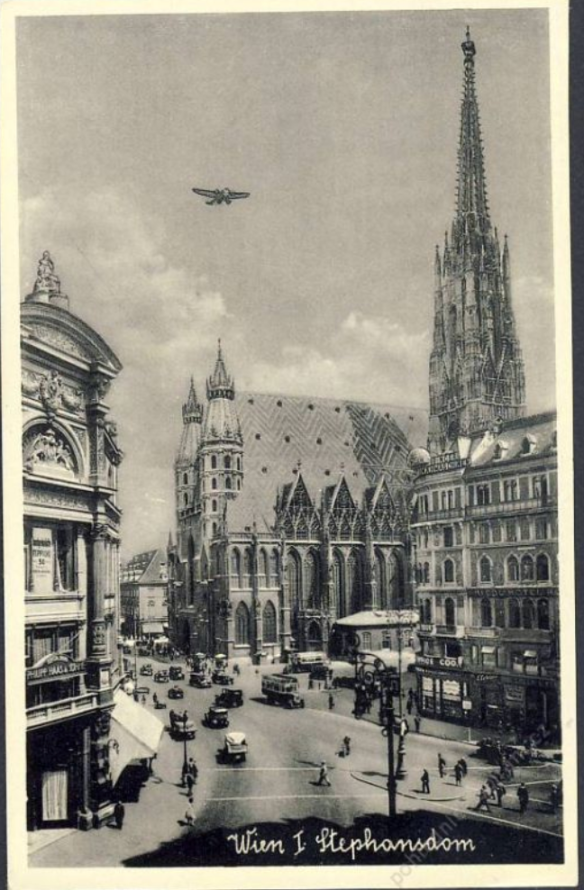

St Stephen’s Cathedral, Vienna, c. 1930 (via pohlednice.sbiram.cz/)

Later, when von Hildenbrand’s wife and son had joined him in Vienna, the Breitenfelds would help them to find an apartment near St Stephen’s Cathedral. It seems likely that Theodor Kern, as a close friend of Dietrich von Hildebrand and a member of the circle that gathered around him in Vienna, would also have come to know Walter and Johanna Breitenfeld at this time. Like Kern, the Breitenfelds were active, after the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, in helping those in danger to escape from the country. And like Kern, this meant that eventually they had to leave Austria themselves. According to Johanna’s obituary:

Non-Jewish, but high on the Gestapo’s blacklist, Walter Breitenfeld managed to escape after the Anschluss: his wife and three small children followed shortly afterwards, pretending to go on a Danube outing. Attaché cases were all the belongings they could take with them. But they were able to reach the family’s property at Futok, near Novisad (Croatia). In 1939 the Breitenfelds came to England to place their children in English schools and were prevented by the outbreak of the war from returning home.

It would appear that, like Theodor and Frieda Kern, Walter and Johanna Breitenfeld chose to remain in England after the war, rather than returning to Austria. In her new homeland, as her obituary relates, Johanna found new outlets for her charitable impulses:

In London Johanna Breitenfeld was instrumental in the founding of the Austrian Catholic Centre at Brook Green, which is run by Sisters of the Gospel, one of the Austrian Catholic Secular Institutes

[…]

In 1951 she joined the Austrian embassy in London as head of the social section, newly formed through the intervention of the Austrian Chancellors Figl and Raab, to help the 30,000 Austrian women who worked in the Yorkshire and Lancashire textile mills when Austria was hit by famine, unemployment, continued occupation and the dismantling of factories in the Soviet zone. She was the first to liaison between these foreign workers and their employers and local authorities. There were many problems due to loneliness and inability to communicate in a strange environment to which these young women, mostly peasant girls, had been transplanted. There was a high suicide rate; some ended in mental homes. Johanna Breitenfeld deliberately styled the embassy work a ‘service’ to differentiate it from the normal bureaucratic functions. Her section was one of the first embassy departments of its kind, and other London embassies followed its example. Although she retired officially in 1966 (she was awarded the Goldenes Verdienstzeichen of the Republic of Austria) she remained in touch with many of her ‘proteges’ and in ‘active service’ to the end of her days.

Walter and Johanna had three children. Their eldest, Elizabeth, who was born in 1929, married Michael Skinner in 1952 and died in 1990. Hubert Breitenfeld, born in 1930, married Norma Turnbull in 1953. They had two sons, Richard John Carl Maria Breitenfeld, born in 1954, and Robert Anthony Maria Breitenfeld, born in 1959. Hubert died in 1999. Walburga Breitenfeld was born in 1932. I haven’t been able to find out any more about her, except that it seems she designed the cover of at least one book:

Cover of ‘The Wild and The Tame’ by Huldine Beamish, Geoffrey Bles Ltd, 1957, jacket design by Walburga Breitenfeld

Walter Breitenfeld died in 1967 and Johanna in 1992, at the age of 93. As fellow Austrian exiles in England, with a shared religious outlook and shared friendship with Dietrich von Hildebrand, it would not be surprising if the Kerns and Breitenfelds remained in close contact in the postwar years. Johanna’s obituary states that ‘everything she did came from the well-ordered storehouse of a fine mind and a large heart formed in the tradition of the Benedictine virtues of ora et labora.’ The mention of Benedictine spirituality makes me wonder whether Walter and Johanna Breitenfeld might have been, like Theodor and Frieda Kern, members of the religious Gemeinschaft inspired by Dietrich von Hildebrand and led by Marguerite Solbrig?

[Update: see this post]

Notes

- The writer of Johanna Breitenfeld’s obituary, the journalist and biographer Roland Hill, was himself a refugee from Nazism. According to his own 2014 obituary in The Telegraph: ‘An only child, Roland Hill was born Roland Johannes Hess in Hamburg on December 2 1920 to parents of Jewish descent who had converted to Lutheran Christianity and who would follow their son into the Catholic Church. His Viennese-born mother was an opera singer; his father was a sugar merchant.’

- Dietrich von Hildebrand (2016) My Battle Against Hitler: Defiance in the Shadow of the Third Reich (translated and edited by John Henry Crosby with John F. Crosby), New York: Penguin Random House

- Alice von Hildebrand (2000) The Soul of a Lion: Dietrich von Hildebrand: a Biography, San Francisco: Ignatius Press