On Friday I had the pleasure of speaking with two people – one face-to-face and the other via Skype – who knew Theodor Kern personally, and who generously offered to share their memories of the artist with me. In the morning I spent some time with Father Andrew O’Dell, a retired Assumptionist priest at the church of Our Lady Immaculate and St Andrew here in Hitchin, and in the afternoon I spoke via Skype with Professor Josef Seifert (see the previous post) at his home in Gaming, Austria.

Our Lady Immaculate and St Andrew, Hitchin (via parish.rcdow.org.uk)

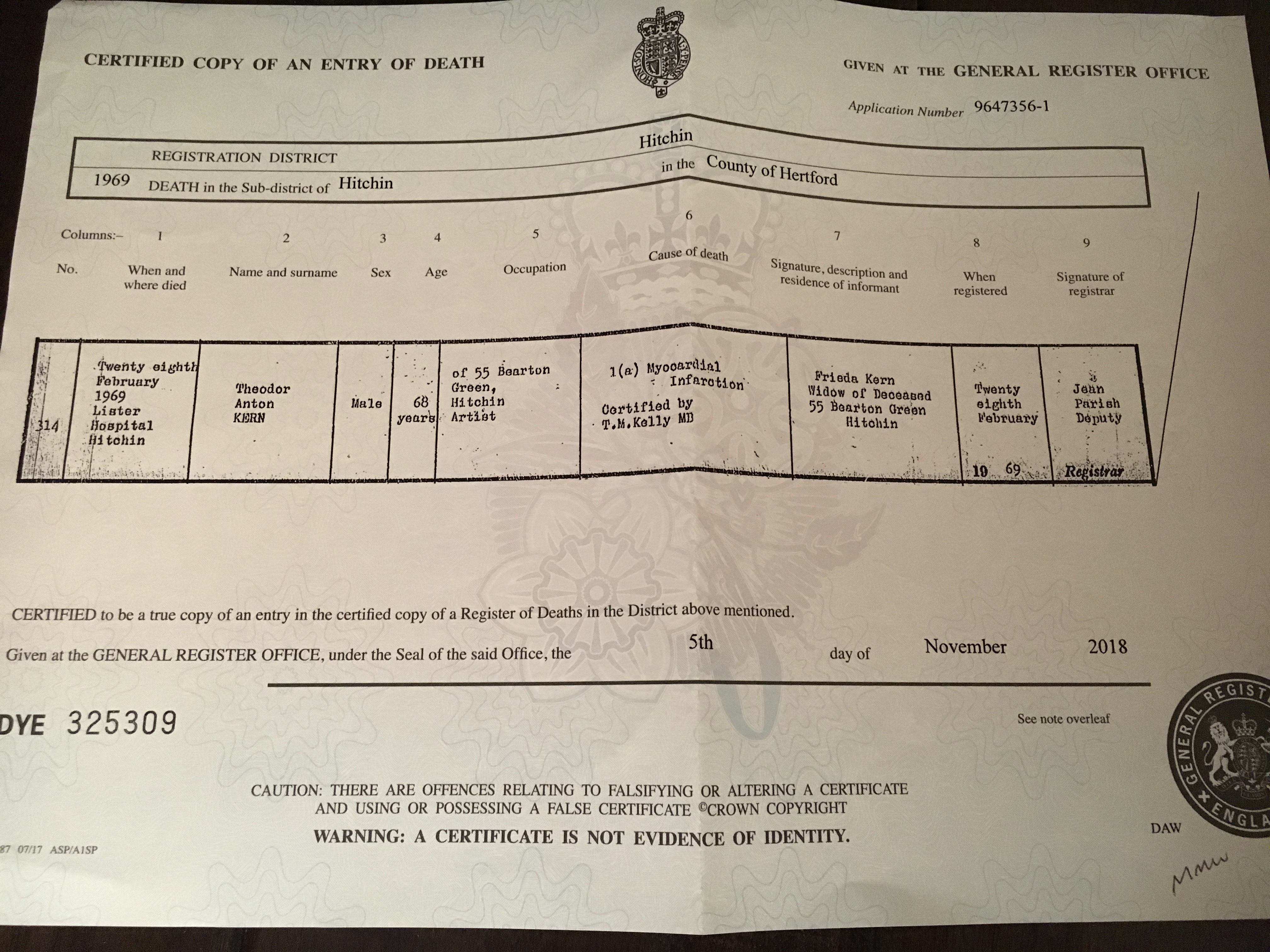

Father Andrew was born in Hitchin and as a child attended the parish church that he would later serve as a priest, which also happened to be the church Theodor Kern attended from the time he settled in the town in the 1940s until his death in 1969. Now in his eighties, Father Andrew was still a child when Theodor Kern was alive, but as a young priest he knew Kern’s widow Frieda quite well. He has a number of childhood memories that involve the artist. For example, he remembers the two wooden statues – of St Andrew and St Michael – that Kern carved arriving at the church in about 1947. Parishioners were told they were made from oak salvaged from the Houses of Parliament after it was bombed. Father Andrew showed me a small plaster model of the statue of St Andrew that Theodor used as a template, and which Frieda gave him:

Father Andrew also has a vivid memory of a talk that Kern was invited to give, by the then parish priest, on the construction of stained glass windows. Father Andrew would have been twelve or thirteen years old at the time, and he remembers being fascinated by the talk. He has a particular memory of Kern inviting him and the other children present to try their hand at glass cutting, and remembers the artist as a natural and gifted teacher. As part of the presentation, Kern displayed a full-size photograph of a stained glass window he was in the process of creating. This was one of two – of Our Lady and St Joseph – that can still be seen in the old church building, which now functions as the parish hall (I’ll try to include photos in a future post). Apparently it took a long time for the parish to pay the full amount for the windows, and there was a retiring collection every Sunday until the total was reached. A third stained glass window was created by Kern and dedicated to the memory of a Mr and Mrs Sell. The window depicts the Sacred Heart to which, Father Andrew said, Mrs Sell had an extraordinary devotion.

It seems that Frieda Kern was enormously proud of her husband’s talent, and particularly of his ability to turn his hand to many different kinds of artistic creation, including painting, stone sculpture, wood carving and glass cutting. She told Father Andrew that, soon after arriving in the area in the 1940s, Theodor had been employed teaching art to patients at the asylum in Arlesey: information that supplements what we already knew about his work with wounded soldiers in hospitals near Hitchin.

One of the Stations of the Cross created by Theodor Kern, church of Our Lady Immaculate and St Andrew, Hitchin

It seems that the Stations of the Cross which now adorn the walls of the church were donated after the artist’s death by his widow. On becoming parish priest in the 1990s, Father Andrew discovered that the images had begun to fade and the materials to decay, so he had them remounted and framed by an art shop in the town. Father Andrew also mentioned a powerful depiction of the story of the Prodigal Son, painted on hardboard, which had stood in the chapel of the former St Michael’s School, but he has no idea what happened to it after the school merged with another to become John Henry Newman secondary school in Stevenage.

We talked a little about Theodor Kern’s many depictions of the Virgin and Child, and Father Andrew recalled Frieda telling him, that in the last week of his life, Theodor was still working on new versions of this iconic image. And Father Andrew confirmed what others have said: that after the artist’s death, hundreds of paintings remained in his studio, and that his widow offered the choice of them to many of their friends, so that there must be a large number of his works in private ownership.

Father Andrew told me another story about Theodor Kern that he heard secondhand, not having witnessed the event himself. Apparently there was a priest at the church who had some highly original notions about the Holy Spirit. He was expounding on these during Mass, when Kern stood up in his pew and shouted out ‘That is heresy!’ It’s not known what happened after that.

The subject of the Kerns’ grave in Hitchin Cemetery came up in our conversation. Father Andrew tells me that it lies in the same part of the cemetery in which the priests of the Assumptionist community in Hitchin are buried. It seems that after Theodor’s death Frieda placed one of his wooden statues beside the grave, but without any protective treatment, so that it decayed over time and was eventually removed.

Schloss Arenberg, Salzburg (via salzburg.info)

Josef Seifert also came into contact with Theodor Kern as a child. His parents, Edouard and Edith Seifert, née Schuchter, were good friends of Theodor and his wife Frieda. The Kerns would travel from their home in Hitchin to Salzburg every summer, staying at the Schloss Arenberg, which was on Arenbergstrasse where Josef’s family lived, in a house belonging to Josef’s grandmother, the author and translator Johanna Schuchter. Josef suggested that his grandmother’s memoir, So war es in Salzburg: Aus einer Familienchronik might be a useful source for my research, so I’ve ordered a copy.

Josef is unsure how his parents came to know Theodor Kern. As I noted in the last post, I believe that Theodor knew the Schuchter family when he lived in Salzburg in the early 1930s, before his final departure for Vienna, and that was how he was able to introduce Edith’s sister Gertrud to her future husband, his friend Hellmut Laun, when she also arrived in the capital. Edith and Gertrud were the daughters of Johanna and her husband, the medical doctor Franz Schuchter, and according to Laun’s memoir were among the first women in Austria to study at university. Edith initially wanted to study in Vienna, but Josef told me that his mother heard an ‘inner voice’ telling her to go to Munich instead, which she at first resisted, but to which she finally surrendered. On her first day at university in Munich, Edith Schuchter met the Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand, a providential meeting that led to a revival of her faith, as well as an introduction to the Hildebrand circle. Josef himself would eventually study with von Hildebrand and would come to be regarded by the philosopher as his intellectual heir. Josef was unable to answer my question about whether his mother had known the future Frieda Kern in Munich, and could not confirm my theory that Frieda, who was Jewish by birth, may have converted to Catholicism under von Hildebrand’s influence.

Grave of Josef Seifert’s parents and grandparents in the Kommunalfriedhof, Salzburg (via findagrave.com)

Whatever the origins of the Seiferts’ friendship with the Kerns, they certainly knew each other as fellow members of the lay religious Gemeinschaft that I’ve mentioned in previous posts, as were many other members of the Hildebrand circle, including von Hildebrand himself, Balduin and Leni Schwarz and their son Stephen, and Hellmut and Gertrud Laun. Josef told me that his mother Edith took over the leadership of the group following the death of Marguerite Solbrig, who had been von Hildebrand’s secretary. Another prominent member of the Gemeinschaft was the jurist Wolfgang Waldstein, who is mentioned in Frieda Kern’s will, and was also apparently a good friend of Theodor. Josef suggested that Waldstein’s memoir, Mein Leben, might include useful references to Theodor, so I have ordered a copy.

Old photograph of the Getreidegasse, Salzburg (via delcampe.net)

Josef, his brother Benedikt and their cousin Andreas Laun (now the emeritus auxiliary bishop of Salzburg: see the last post) all have fond memories of Theodor Kern from their childhood. Josef remembers Theodor as a wonderful, kind man, an extraordinary person with a deep commitment to his Catholic faith. But, as others have suggested, Theodor was also someone with a great sense of humour, even of mischief. Josef recalls listening to the artist tell the children stories of his own childhood. These included the time when Theodor and his family had a house in the cemetery of which his father as director, and one day Theodor threw tomatoes down from a high window into the tall hat of a passing visitor. When some of these missed and smeared the man’s glasses, Theodor’s father Johann Kern was outraged and insisted that his son go to the man’s house in the Sigmund-Haffner-Gasse and apologise. Apparently Theodor’s victim was so surprised and impressed by this gesture that, rather than being cross with the boy, he treated him to some cake. On another occasion, Theodor and his friends got up on the roof of a building in the Getreidegasse (the busy shopping street where Mozart’s birthplace is located), which attracted the attention of the local police. But Theodor somehow found his way down, and joining the crowd below, tried to distract the officers by sending them in the wrong direction. A third story related to Theodor’s mother’s attempts to stop him getting holes in his lederhosen. She bought him a pair that she insisted would be impossible to damage, but Theodor immediately used one of his father’s gardening tools to make a hole in the lederhosen, to prove his mother wrong.

I’m immensely grateful to both Father Andrew and Professor Seifert for taking the time to share their memories of Theodor Kern. My conversations with them have enriched my understanding of Theodor Kern the man and have given me some promising new ‘leads’ to follow up in my research.